Soils

Maintaining healthy soils is critical to support a healthy environment and our food production. Issues such as wind and water erosion, soil acidification and salinity, declines in soil structure, fertility and water absorption capacity all need to be addressed, particularly in the face of climate change.

Soil health is the ability of soil to function as a living ecosystem in relation to its natural capacity. A healthy soil:

- is fit-for-purpose

- sustains biological productivity both above and below ground

- maintains landscape function and environmental quality

- regulates our climate by storing carbon and influencing temperature

- provides habitat and promotes plant, animal and human health

- is productive, resilient and profitable.

A total of 61 different soil types have been mapped across South Australia.

Wind and water erosion poses the biggest threat to agricultural soils in South Australia and is likely to become exacerbated with climate change. Approximately 5.4 million hectares (61%) of agricultural land is susceptible to wind erosion and 2.9 million hectares (32%) to water erosion.

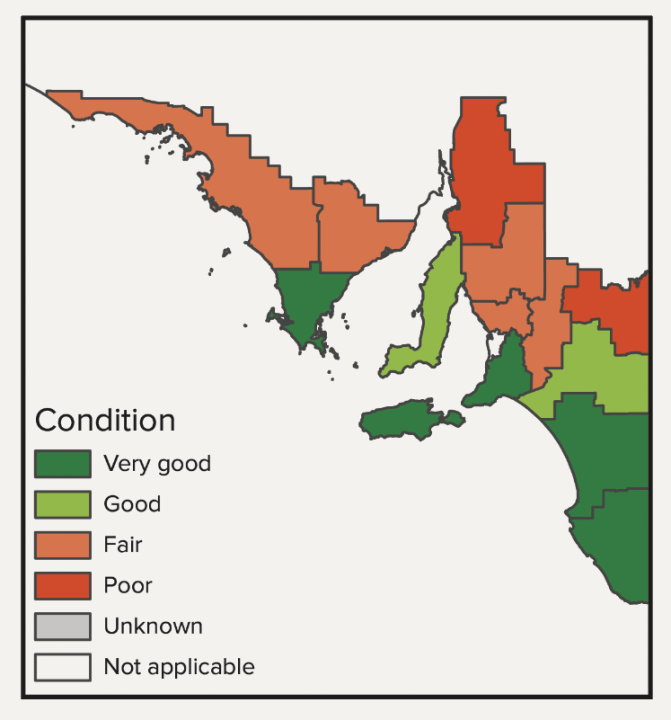

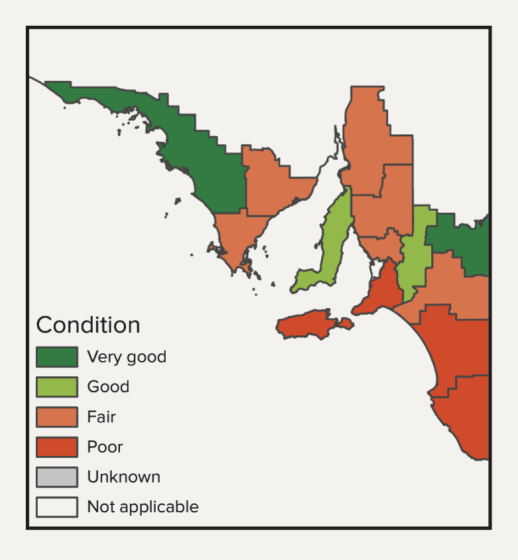

The level of soil erosion risk varied across agricultural districts. Seven districts that are in higher rainfall areas had a 'very good' or 'good' condition rating. The Upper North and Northern Mallee districts had a 'poor' condition rating due to well-below average rainfall in most of the past five seasons.

Soil erosion risk on agricultural land has been getting worse over the past five years most likely due to declining rainfall resulting in less plant growth and, therefore, ground cover to protect soil from erosion. This trend is observed for 6 of the 14 agricultural districts located in lower rainfall areas. The trend for the remaining 8 districts is considered to be stable.

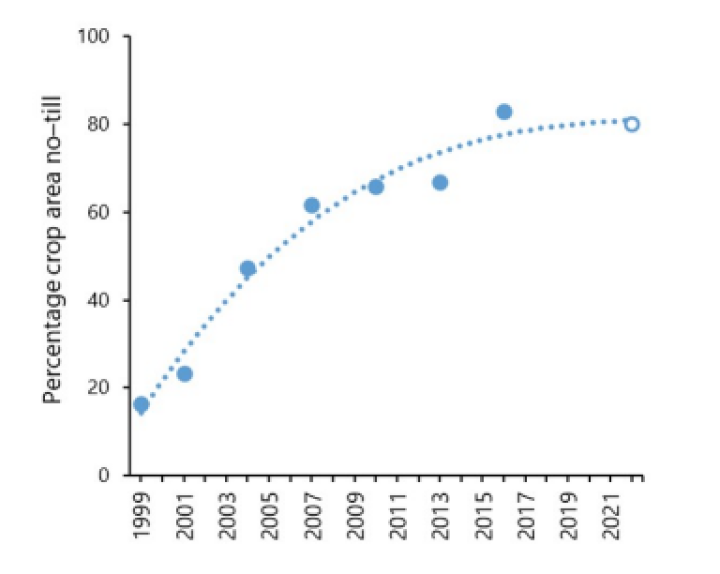

No-till sowing is being adopted by farmers to reduce the risk of soil erosion. The adoption of no-till sowing for annual crops has increased from 16% in 1999 to 83% in 2016. No-till sowing has now stabilised at around 80%, which is considered to be very good. Other improvements in farming practices, such as stubble retention and managing stock grazing, are also being implemented to help minimise soil erosion.

The extent of soil acidity differs across the agricultural districts, with districts exhibiting higher soil acidity in areas that have higher rates of naturally occurring acidic soils. The trend in agricultural soil acidity has been getting better since 2018 with the use of lime.

Approximately 3.9 million hectares (44%) of agricultural land in South Australia is considered at risk of acidity. Of this, about 2.5 million hectares (28%) are already close to or at pH levels that are too acidic, which is reducing the yield of crops and pastures. Soil acidification is a natural process in the higher rainfall areas of South Australia, but can be significantly accelerated by agricultural practices.

Around 1.5 million hectares of cleared agricultural land is affected by watertable-induced dryland salinity with the Upper South East and areas of Eyre Peninsula most impacted. Dryland salinity also impacts native vegetation and infrastructure such as roads, sewers and buildings. Natural (or primary) salinity can be a feature of some soils and waterbodies. However, human-induced (or secondary) salinity can arise where land use and management activities lead to increased intensity or extent of salinity in the landscape.

Soil acidity and dryland salinity are major threats to the health of our soils and impact agricultural productivity.

Soil acidity can pose a key threat to the productivity of agricultural land. Currently, around 2.5 million hectares (~28%) of cropping land in South Australia has become, or is close to becoming, acidic, which costs the industry in lost crop and pasture production around $89 million per year. Annual lime use, to increase productivity of soil, has increased by approximately 200,000 tonnes (tripled) since 2016. The area impacted by soil acidity is expected to rise by 3.9 million hectares over the next 30 years if remedial action is not taken. Soil acidity is a natural feature, but can be significantly accelerated by agricultural practices on certain soils.

Dryland salinity also poses a threat to agricultural land. In addition, salinity impacts native vegetation and infrastructure such as roads, sewage and buildings. It is usually caused by vegetation clearance and replacing vegetated areas with shallow-rooted annual crops and pastures. This results in rising groundwater, which brings salts to, or near to, the soil surface. Excess irrigation can also result in soil salinisation due to rising watertables. Around 1.5 million hectares of cleared agricultural land is affected by watertable-induced dryland salinity, with the Upper South East and areas of Eyre Peninsula most impacted.

Some farmers are adopting regenerative agriculture practices that provide a more holistic and sustainable approach to farming and land management. These practices focus on restoring and enhancing the health and vitality of soils and ecosystems. The primary goal of regenerative agriculture is to improve the overall health of the land while also increasing agricultural productivity. It is often considered a response to the environmental and ecological challenges associated with conventional agricultural practices, as undertaken in the following regions:

Further reading

- Soil and land management – Resources produced by the Department for Environment and Water on:

- description of the soils of South Australia: Department for Environment and Water – Soils of South Australia

- importance of maintaining healthy soils: Department for Environment and Water – Maintaining Healthy Soils

- soil health and condition: Department for Environment and Water – Soil Health and Condition

- sustainable soil and land management: Department for Environment and Water – Sustainable soil and land.

- The Agricultural Bureau of South Australia – Information on projects to improve health and productivity of agricultural land and information on soil health and management.

- Australian Water Outlook – An interactive map from the Bureau of Meteorology for soil moisture, runoff, evapotranspiration and precipitation.

- Soil Protection Progress Report July 2021 – Report by Department for Environment and Water on monitoring of soil erosion.

- Soil Carbon in South Australia Volume 1: Soil Carbon Forward Plan – A plan produced by DEW in collaboration with PIRSA and Landscape SA to help inform development, policies and actions to help protect and improve productivity of soils and, hence, long-term storage of carbon in agricultural and rangeland soils.