- Home

- Environmental Themes

- Liveability

- Water Supply

Water Supply

In South Australia, water is managed and monitored by a number of different agencies. This includes natural environments (surface waters, marine waters and groundwater), drinking water, water used for other purposes (for example, irrigation), wastewater and stormwater.

SA Health regulates the provision of safe drinking water as supplied to consumers under the Safe Drinking Water Act 2011. SA Water is primarily responsible for the supply of drinking water to the public in South Australia.

Sources of Water

River Murray

The River Murray is our main source of water in South Australia, which supplies around 50% of our drinking water. South Australia receives 1,850 GL per year under the Murray–Darling Basin agreement. This may be reduced during dry conditions.

The South Australian Government has appointed a Commissioner for the River Murray to advocate for the health of the Murray, Lower Lakes and Coorong in South Australia. This also includes securing the delivery of 450 gigalitres of environmental water to the River Murray by 2024 as specified in the Murray-Darling Basin plan. So far, only four gigalitres has been achieved. The Basin Plan is currently being reviewed with an agreement by the Australian Government for the delivery of 450 GL of environmental water by 2027. This will be achieved with the introduction of the Water Amendment (Restoring Our Rivers) Bill 2023 to the Australian Parliament to amend the Water Act 2007. This Bill has now been passed by the Australian Parliament.

Here is a video showing how water from the River Murray is shared between states.

Reservoirs

South Australia has 10 reservoirs that have the capacity to supply around 200 GL to the Greater Adelaide region. This is equivalent to a year’s supply of water. The majority of water for these reservoirs is sourced from rainfall and connecting waterways. However, they can be used as storage for River Murray water during periods of high demand. Another six reservoirs are in regional South Australia, with three of these being used for drinking water supply. SA Water is responsible for managing our reservoirs.

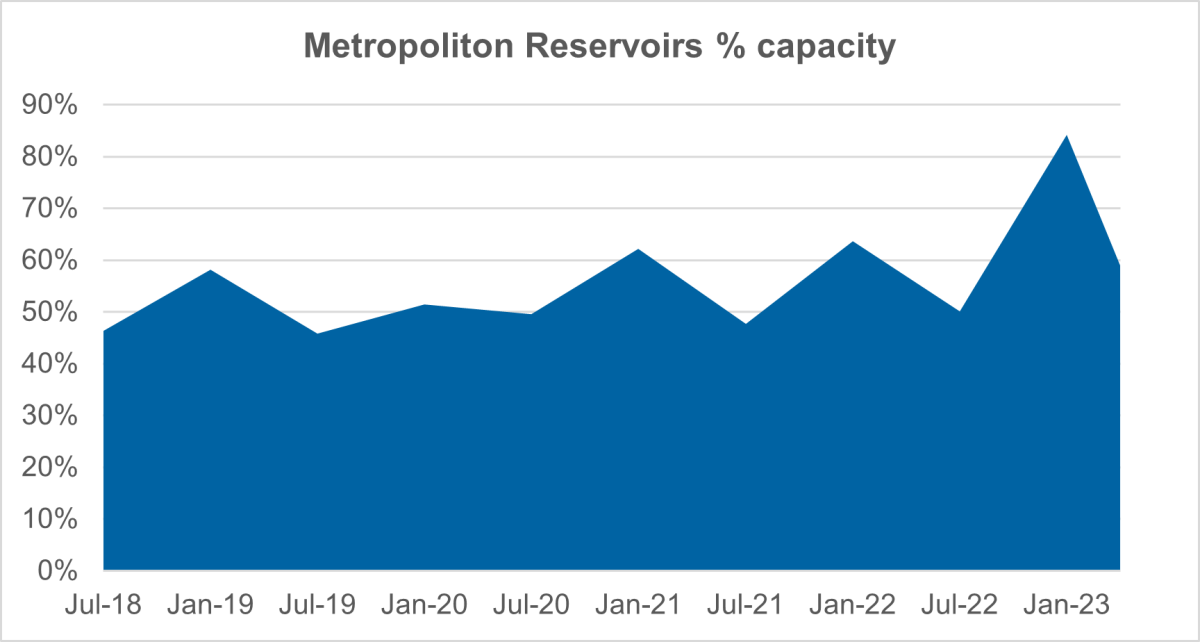

Percentage capacity has remained relatively stable in our metropolitan reservoirs since 2018, except for January 2023 when it reached 84%. Much of this increase occurred in Mount Bold, South Para and Kangaroo Creek reservoirs.

Many reservoirs have now been opened to the public for recreation, including fishing, kayaking and cycling. Myponga, located on the Fleurieu Peninsula, was opened in April 2019. Since then, a total of 11 reservoirs across the state have been opened. As of May 2023, our reservoirs have welcomed over one million visitors and support the health and wellbeing of our community. Happy Valley (with 320,000 visitors) and Myponga (200,000) are our most visited reservoirs. Some reservoirs have also been stocked with native fish species and support conservation activities.

A number of reservoirs across the state are no longer used for water supply due to various factors, for example, the Tod River Reservoir is no longer used due to a deterioration in water quality from dryland salinity and agricultural chemical runoff.

Desalination plants

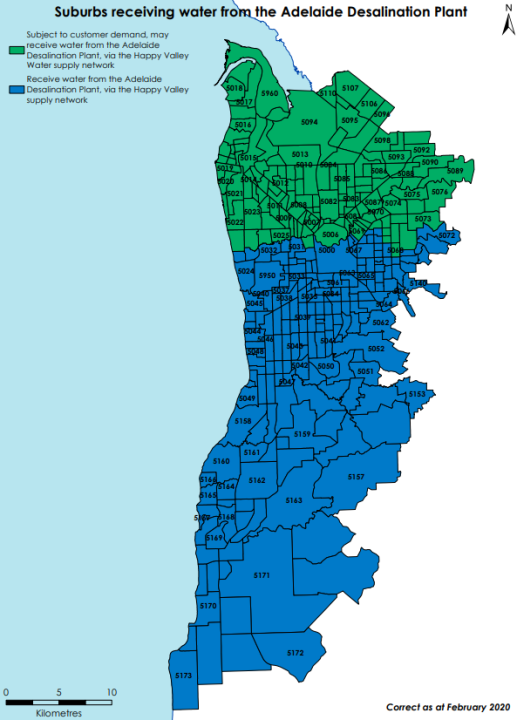

There are 11 desalination plants across South Australia that supply clean and safe drinking water to people. Two plants treat sea water, and these are located at Lonsdale and Penneshaw. The other nine plants provide water to remote Aboriginal communities and regions around Leigh Creek, Hawker and Oodnadatta by treating saline groundwater.

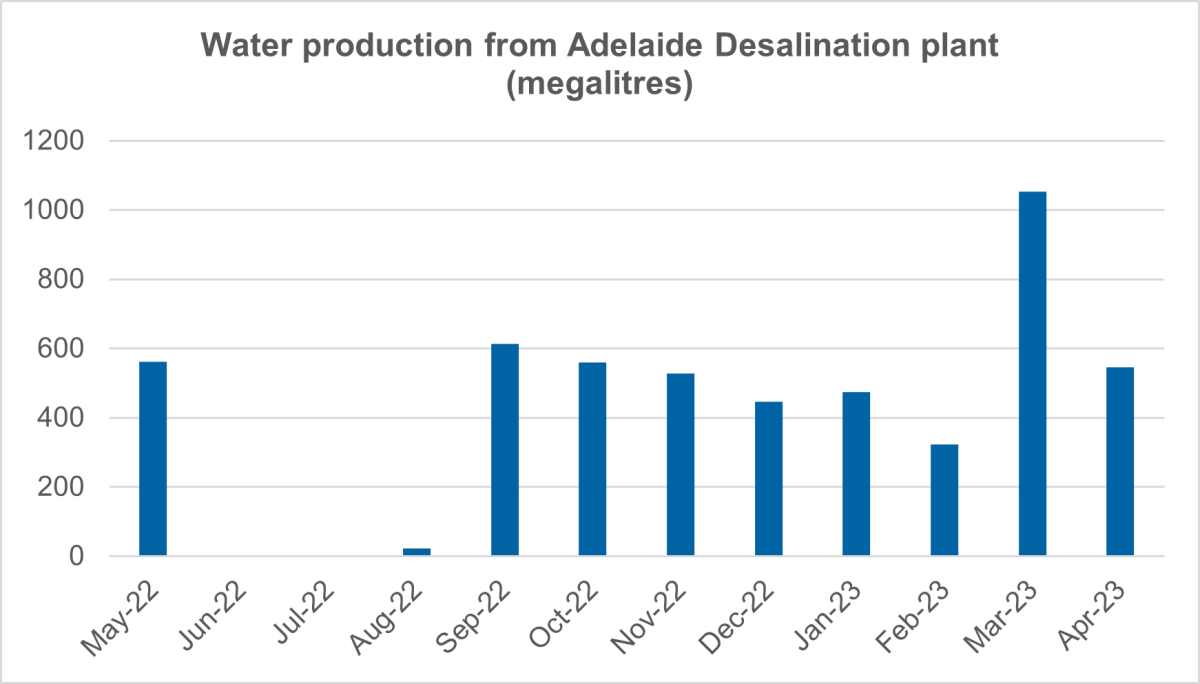

Production from the Adelaide desalination plant at Lonsdale is dependent on rainfall and water demand. It has the capacity to produce around 100 GL/year, which is around 50% of Adelaide’s water supply. Construction of the desalination plant was primarily in response to the millennium drought that was experienced in South Australia from 2001 to 2009.

Recycled water

Recycled water can be used for a number of non-potable purposes, that is, not for drinking or food preparation. SA Water supplies treated water from their wastewater treatment plants predominantly for garden watering, toilet flushing, industrial use and irrigation.

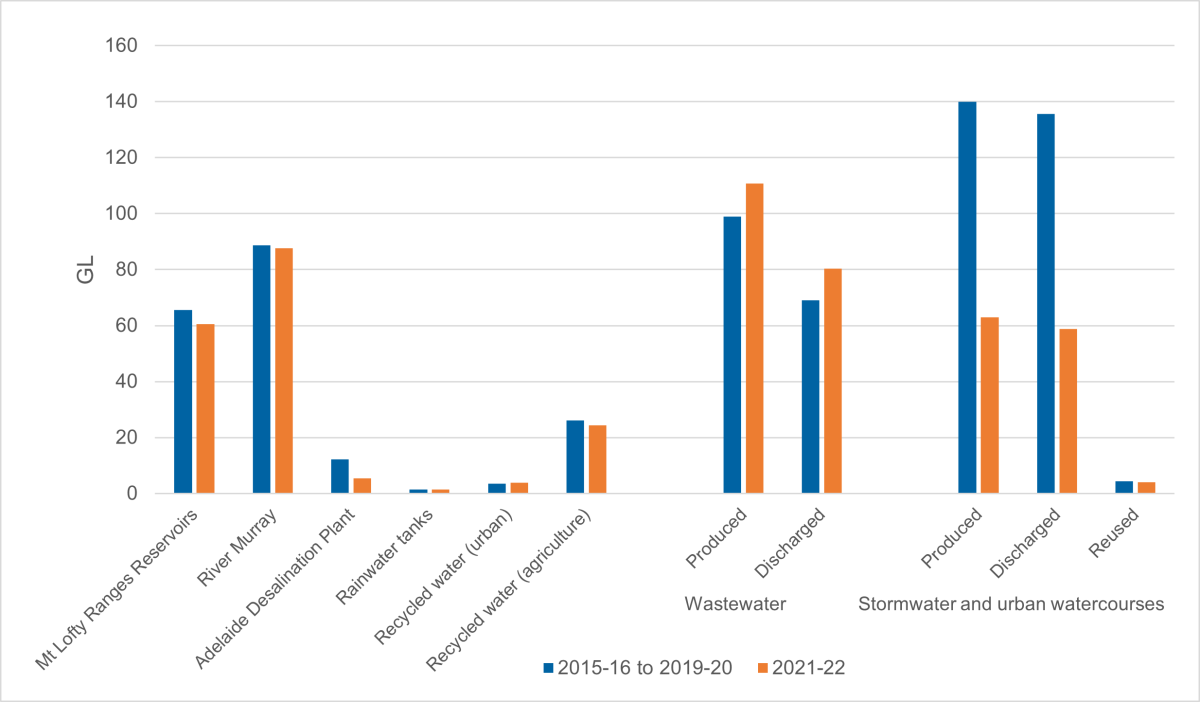

Adelaide is leading the way for water recycling and, from 2015 to 2020, has significantly increased capacity, nearly equaling Melbourne in the volume of water that is recycled each year. However, more can be done in this space, with 70% of treated wastewater still being discharged into the aquatic environment.

Groundwater

Water is sourced from groundwater where rainfall is inconsistent or is used by industry and some towns and residential properties. Groundwater allocation is predominantly managed by the Department for Environment and Water via licensing and Water Allocation Plans. DEW also monitors groundwater to ensure it is sustainably managed.

SA Water and some councils are adopting Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) where water is stored in aquifers during winter for later reuse during summer when irrigation needs are greater. There are now over 40 MAR schemes operating across the Greater Adelaide metropolitan area that have injected 48 GL of water for non-potable uses.

People also source water from dams, waterways and rainwater. Smaller and more remote communities rely on more local sources for their water, which can often have a lower standard of supply and quality compared with more urban areas.

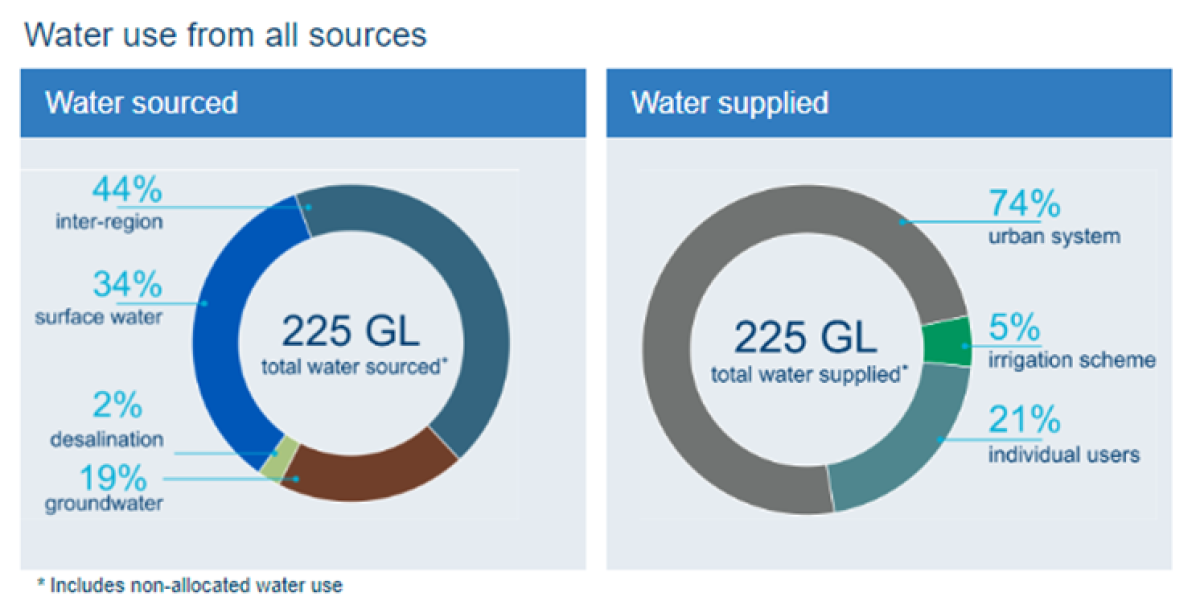

Water Use

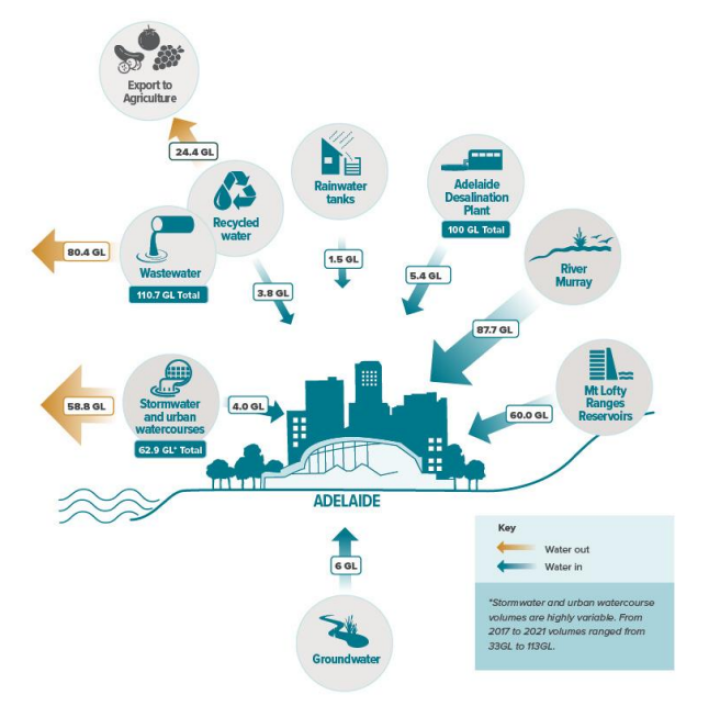

The Bureau of Meteorology National Water Account for Adelaide for 2021-22 indicated that 225 GL was sourced and supplied to Adelaide, which was similar to the year before. South Australia’s water supply is predominantly sourced from the River Murray (44%) followed by surface water (34%), groundwater (19%) and desalination (2%).

It is estimated that 80.4 GL of wastewater (73%) and 62.9 GL of stormwater (93%) is discharged to the environment every year. There has been very little change in the volume of wastewater and stormwater recycled for urban or agricultural use and water sourced from rainwater tanks. This represents an opportunity for the harvesting and reuse of this water to help secure water supplies for Greater Adelaide and regional centres. Better use of greywater and rainwater tanks could also help secure our water supplies.

Water sensitive design that retains rain where it falls has multiple benefits, including more natural flow regimes and retention of water for greening to help mitigate the urban heat island effect. Installation of water sensitive features such as permeable paving (for example, for carparks and footpaths) reduces stormwater runoff and enables the recharge of groundwater.

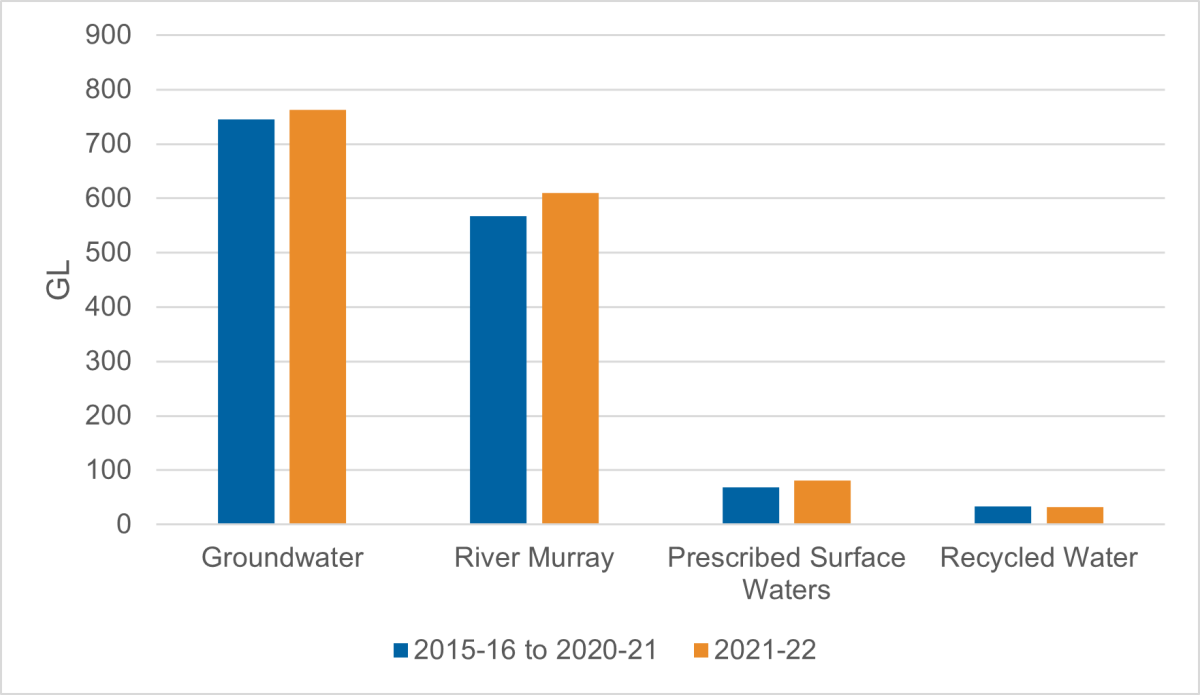

Across South Australia during 2020–21, water use from groundwater and surface waters slightly increased, recycled water use remained stable and water produced from Adelaide’s desalination plant decreased. This is compared with average water use between 2015–16 and 2019–20.

Groundwater – is used for irrigated agriculture, forestry, domestic supply, stock, mining, industrial applications and irrigation of recreational and sportsgrounds.

River Murray and Prescribed Surface Waters – capacity from surface waters relies on rainfall. Water use for 2021–22 was higher than previous years, largely due to increased water availability.

Recycled Water – includes the capture and re-use of stormwater and the re-use of wastewater.

Desalinated Water – the majority of desalinated water is produced by the Adelaide desalination plant which has a capacity of 100 GL. A further 0.4 GL was produced by plants servicing regional communities.

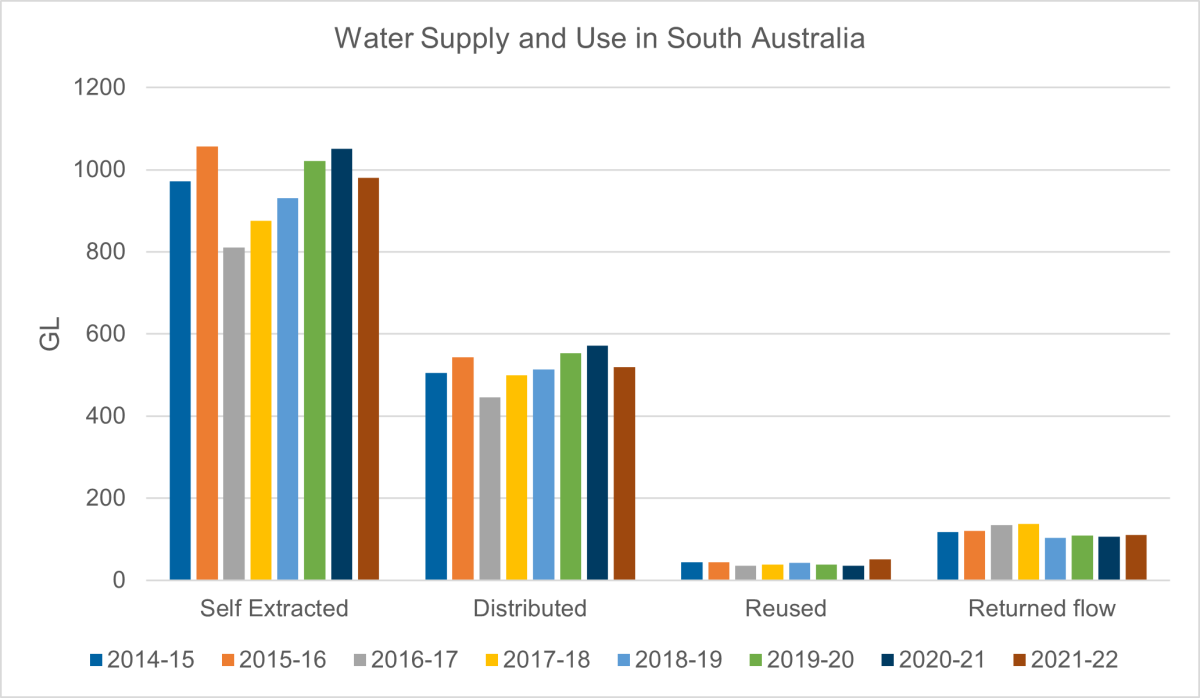

Self-extracted – Water that is extracted directly from the environment. Possible sources include surface water (e.g. rivers and lakes), groundwater and desalinated sea water.

Distributed – water supplied by SA Water, irrigation trusts and local councils.

Reused – Wastewater (including sewage) that is collected, on-supplied and used again by other businesses/households. It may have been treated to some extent. Reuse water is also known as recycled water or effluent re-use.

Returned flows – the return of water by the water supply, sewerage and drainage services industry (the majority of which was treated wastewater) to the environment with much of it being discharged out to sea.

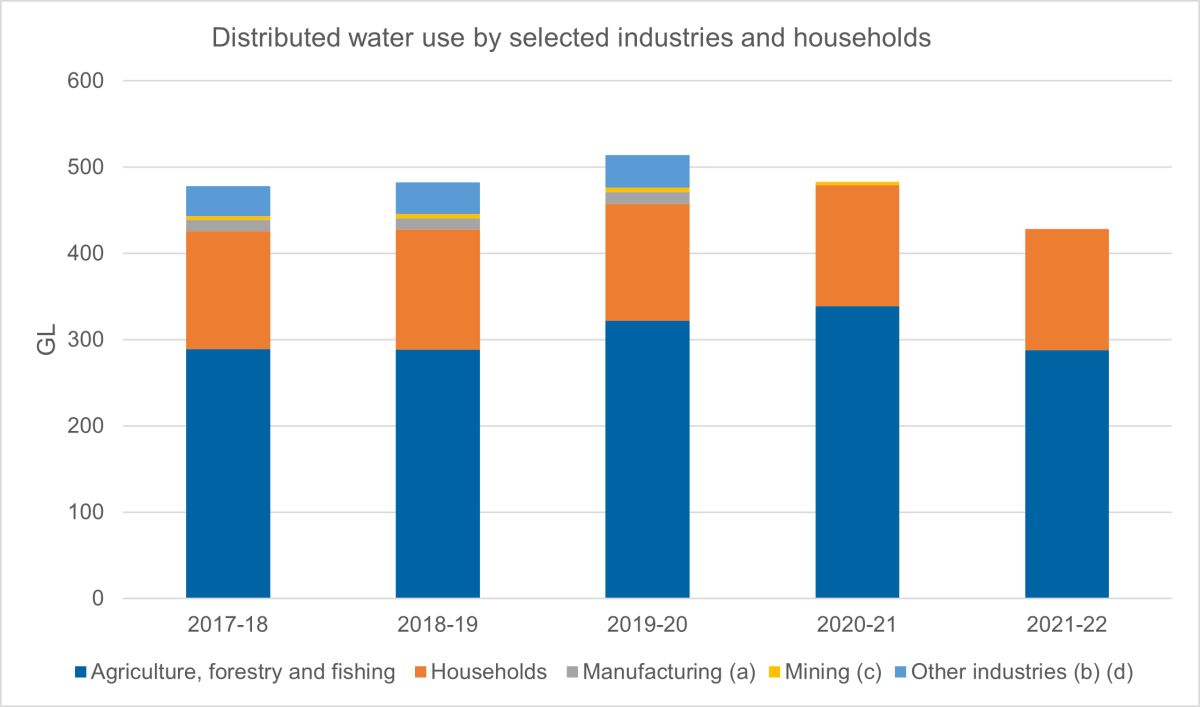

Distribution of water in South Australia is driven by demand from the agricultural, forestry and fishing industries followed by households. Between 2020–21 and 2021–22, distributed water use decreased by 15% for agriculture, forestry and fishing (compared with an increase of 8% nationally). Distributed water to households increased by 4% between 2019-20 and 2020-21 and has remained stable since then whereas, nationally, it decreased by 2% (ABS Water Accounts 2021–22).

Note: Data was not available for publication for manufacturing (a) and for other industries (b) in 2020–21 and 2021–22 and not available for mining (c) in 2021–22. Other industries (d) does not include electricity or gas supply or water supply, sewerage and drainage service industries.

Protecting our Water Supply

Pressures

- An expanding population that will increase demand on water supplies required for irrigation (including maintaining green space, livestock, crops, orchards and vines) and potable use. This demand is likely to increase further with climate change, with increasing temperatures and evaporation, and declining rainfall.

- Urban sprawl and infill increasing the area of impermeable surfaces, therefore affecting the penetration of water into soils and groundwater supply.

- An ageing drainage and sewer network that is built for a lower population density.

- Lack of infrastructure, planning and services to deliver a reliable and safe water supply to some regional and remote communities.

Impacts

- Reduction in water availability needed for potable uses, irrigation, livestock, industry and other needs (potentially food and water supplies), and other services and products.

- Cost of water potentially becoming more expensive as alternative methods for accessing water need to be implemented, for example, operation of desalination plants. These methods may result in other environmental risks.

- Less water available for the environment. This may impact groundwater supplies and affect aquatic ecosystems that rely on adequate streamflows, water quality and flow regimes.

- Lack of permeable surfaces may increase the risk of flooding causing damage to housing and other infrastructure. This may also result in increased runoff capturing pollutants such as rubbish and organic matter that is then discharged into urban streams, rivers and the marine environment.

- Our capacity to maintain green space and recreational areas in our built environment may be compromised. Urban heat mapping in western Adelaide undertaken during a hot weather event in 2017 showed that irrigated grass can reduce surface temperature by up to 200C compared with dry grass, and irrigated shade trees can cool the ground by more than 2-30C during the day and 4-50C at night.

Responses

- An Urban Water Directions Statement 2022 was produced by state government to deliver state-wide water management of urban water (drinking water, wastewater services, stormwater drainage, recycled water and natural water systems).

- A Water Security Statement 2022 has been produced by DEW, which provides an overview of South Australia’s water security and future demands in the face of climate change. It identifies 10 strategic priorities that aim to:

- understand and adapt to the impacts of climate change on water security

- work with key stakeholders to develop targeted water security strategies

- ensure the sustainable use of water resources

- meet the critical human water needs of all South Australians including those who live in remote communities

- drive the implementation of the Murray-Darling Basin Plan

- ensure that Aboriginal peoples have appropriate access to water resources for cultural and economic purposes

- manage our urban water resources to adequately support water supply for households and manage wastewater and stormwater in an expanding population

- implement the recommendations of the 2021 review of the Water Industry Act 2012

- invest in data management to identify risks and opportunities and support decision-making

- work with the water sector to build South Australia’s capacity to respond to future water challenges.

- SA Water is now working with the EPA, DEW, LGA, Green Adelaide and Planning and Land Use Services to develop a Resilient Water Futures strategy to deliver an urban water security plan to ensure a secure and sustainable water supply for the future.

- SA Water operates 11 desalination plants to produce potable water for the community, especially in times of drought. Water security plans are also produced by SA Water to project and plan for future water supply requirements.

- The Northern Waters project aims to deliver a water source to the Far North, Spencer Gulf and eastern Eyre Peninsula regions of South Australia involving the construction and operation of a 260 ML/day sea water desalination plant.

- Water Sensitive SA supports options to improve and manage stormwater quality, including WSUD that incorporates better use of stormwater in the urban environment.

- New dwellings with a roof size of over 50 m2 must include an extra water supply, such as a rainwater tank, which is plumbed to a toilet, water heater or cold laundry tap.

- The SA Drought Resilience Adoption and Innovation Hub has been established to help prepare farms and communities in South Australia

Opportunities

- Integrated management of our waters including further provisions for reusing and recycling treated wastewater and stormwater and optimising water use, would provide a more holistic and consistent approach across the state for the governance, management and use of our waters to support water security, public health, environmental and urban amenity outcomes. This would also take the pressure off our drainage and sewer networks, all of which are ageing and built for a lower population density.

- With regard to urban Adelaide’s water balance, 73% of Adelaide’s treated wastewater and 93% of urban stormwater is discharged out to sea. Further investigation needs to be undertaken to harvest and reuse this water for irrigation.

- Provide incentives to install rainwater tanks to capture rainfall at existing residential properties and increase the minimum capacity of rainwater tanks required for new dwellings from 1,000 litres to a capacity in proportion to the land and dwelling size to enable more water to be captured and used.

- Encourage and improve the reuse of grey water and recycling of stormwater for gardens.

- An increased reliance on recycled and privately stored water may require a separate strategy that considers: a) a revision of legislation and/or regulations to promote use of such waters, b) modelling of water use under different scenarios of recycled and stored water usage, c) any improvements required for quality and safety monitoring of such waters (such as in tanks) and d) potential environmental cost-benefit analysis of using such waters.

- Expand the use of managed aquifer recharge where treated stormwater is recharged back into groundwater for later use.

- Incentives to purchase appliances with higher water efficiency ratings and increase registration of appliances under this scheme.

Further Reading

- South Australian Water Use Data ABS

- National Water Account 2022 – Information on Greater Adelaide’s water use and supply including management and regulation.

- Water Security Statement 2022 – Provides an overview of South Australia’s water supplies and demands and its strategic priorities to ensure long-term water security.

- Urban Water Directions Statement 2022 – Supports the integrated management of urban water that will set up our towns and cities for the future.

- Annual Water Security Update 2023 – Information on urban Adelaide’s current and future water security, a snapshot on water security within the regions and addressing current and future risks to water security.

- Research into water for cities and people – Work undertaken by the Goyder Institute into integrated water management.

- Resilient Waters Futures – A strategy developed by SA Water in collaboration with DEW, EPA LGA, Green Adelaide and PLUS to deliver an urban water security plan to ensure a secure and sustainable water supply for the future.

- Future urban water management options for a vibrant and resilient Adelaide – A report by the Goyder Institute for Water Research on recommendations for the future management of urban water and urban waters to support a vibrant Adelaide.

- Falling through the gaps 2021 – A report commissioned by the South Australian Council of Social Service on a practical approach to improve drinking water services for regional and remote communities in South Australia.