- Home

- Environmental Themes

- Waters

- State of our Waters

- Natural Surface Waters

Natural Surface Waters

Inland waters consist of creeks, rivers, wetlands, lakes and other natural water bodies. They can either be fresh or salty. Due to our dry climate, many inland waters have variable flows that are reliant on rainfall. Some inland waters remain dry for years and do not flow unless there is sufficient rainfall.

The Murray–Darling Basin is Australia’s largest river system and

catchment, with 700 km of the total 2,375 km of river winding through

South Australia.

Check out

South Australia also supports the largest salt lake in Australia, which is Lake Eyre. It is the lowest point of Australia, being 15 m below sea level, and is 144 km long and 77 km wide. Lake Eyre actually consists of two lakes, those being Lake Eyre North and Lake Eyre South that are connected by the 16-km Goyder Channel. Lake Eyre is known as Kati Thanda by the Arabana Aboriginal people who help co-manage the Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre National Park with the South Australian Government.

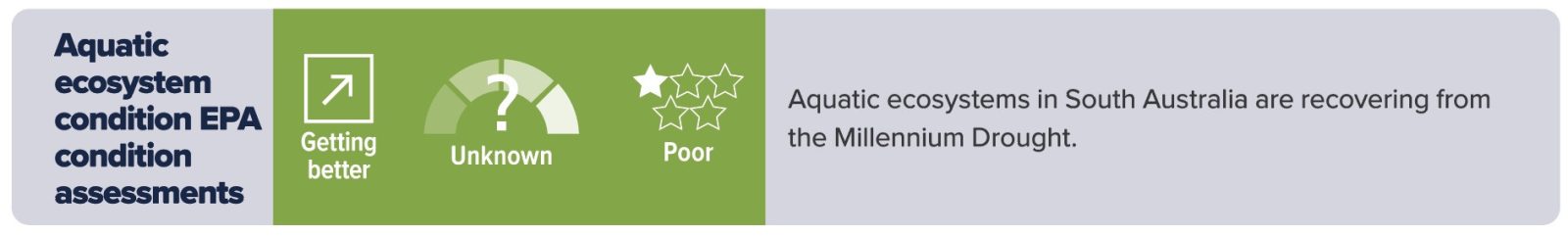

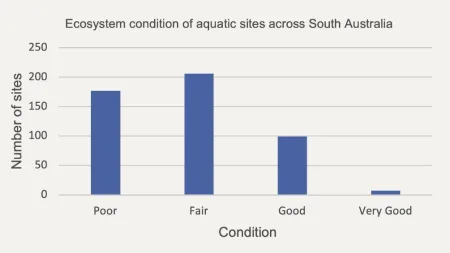

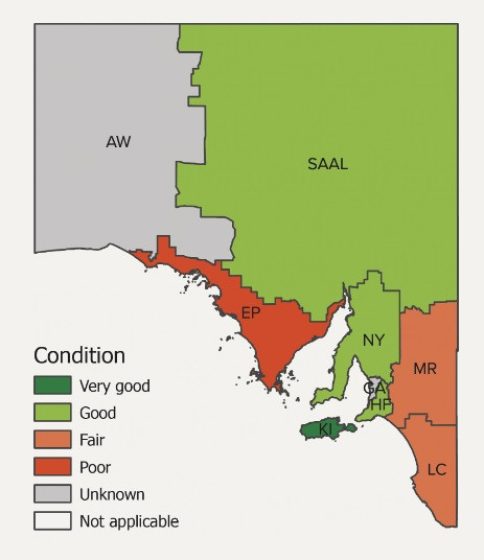

However, since the commencement of the EPA’s aquatic ecosystem condition monitoring in 2008, ecosystem condition of inland surface waters has not appeared to have improved in general, with many sites across South Australia still considered to be in ‘Fair’ or ‘Poor’ condition based on results from the most recent sampling period across the state.

This is likely to be due to a lack of improvement in land management practices being implemented at the site, reach or sub-catchment scale to reduce the movement of nutrients and fine sediment into streams and the presence of riparian weeds. In addition, decreased rainfall and declines in streamflow may cause the loss of flowing freshwater habitats in spring and result in the degradation of stream condition. This could lead to the local extinction of rare and sensitive aquatic species in some regions.

Streams in poorer condition were usually located in cleared agricultural and urban areas, with their condition resulting from stormwater inflows, channelisation, stock and feral animal access, weed invasion and occasionally point-source discharges from industries. These streams were often nutrient enriched, had moderate to high salinity levels, were silted and exhibited degraded riparian habitats comprising introduced grasses and other weed species, with few or no native plants.

Streams in poorer condition also lacked rare and sensitive species, and were dominated by more tolerant and generalist species of macroinvertebrates. High salinity streams (greater than 3,000 to 5,000 mg/L) favoured the presence of only salt tolerant species and affected streams in largely cleared catchments on Eyre Peninsula, eastern Kangaroo Island, parts of the Eastern Mount Lofty Ranges and the western Lake Eyre Basin.

Inland surface waters classified as being in good to very good condition typically occurred where large areas of native vegetation have been retained and where water flows occur in spring. These waters were characterised by the presence of a diverse range of rare, sensitive and flow-dependant macroinvertebrates, and typically had waters with low salinity and low to moderate nutrient concentrations.

Creeks in better condition were generally located in areas with higher rainfall and less disturbance from human activities, including urban development and agriculture. These included some streams located in the Mount Lofty Ranges, Fleurieu Peninsula and western end of Kangaroo Island, or in lightly grazed freshwater stream catchments from the Flinders Ranges and Lake Eyre Basin.

Given the limited occurrence of waters in good to very good condition remaining in the state, further work is needed to identify actions that will improve monitoring and sustain high-value aquatic communities, particularly with the increased risk of extended drought periods under a warming climate with reduced late winter to early summer rainfall that is expected in the future.

Wetlands

In 2020, the percentage of wetlands cover was 1.9% statewide. This is based on an estimated extent of 1,903,100 hectares (ha). Due to recent changes in the sensors and accuracy of satellite data, it is currently not possible to assign a trend to percentage cover of wetlands. The condition of wetlands percentage cover is unknown, as there are no agreed statewide benchmarks.

Extensive reduction in wetlands occurred prior to satellite observations. For example, in the southeast of the state, more than 1.6 million ha of wetlands (over 50% of the area) were converted to agricultural land by various drainage schemes.

South Australia has 1,903,100 ha of wetlands that include 6 Ramsar wetlands that appear on the List of Wetlands of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention and are included because of their ecological, botanical, zoological, limnological or hydrological importance. Wetlands are an important ecosystem as they perform functions such as improving water quality and supporting some of the most biologically productive and diverse habitats on earth. They are also very important culturally to Aboriginal peoples.

Native Fauna and Flora

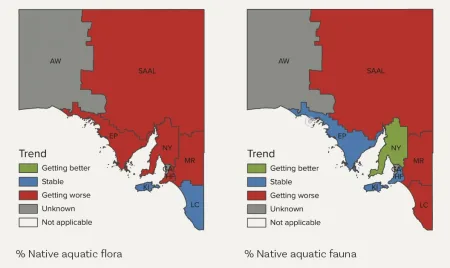

When compared with a 2002 baseline, the 2022 assessment of percentage of native inland aquatic fauna and flora species declining showed variations in trend across Landscape Board regions. However, the overall trend has stabilised across the state.

Protection of our native species is governed under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 including in South Australia. The conservation of aquatic native flora and fauna is also protected in South Australia under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972,

The Threatened Species Action Plan 2022–2032 coordinated by DCCEEW identifies 20 priority habitats and 110 species for protection. In this plan, Kangaroo Island has been identified as a priority location, and a number of plants and animals, including aquatic species, have also been listed

Invasive Species

The trend in abundance and distribution of invasive species of fish, weeds and invertebrates is stable for SA Arid Lands, Murraylands and Riverland, Hills and Fleurieu and Green Adelaide, with these regions considered to be in poor condition. Trends for the remaining landscape regions are unknown due to limited data. The presence of invasive species is found in almost all waterways. However, there have been no reports of any spread to new regions.

Nine new incursions of invasive species were reported to the South Australian Government from 2019 to 2022. However, these were located in backyard ponds and retail settings and, therefore, could be controlled and destroyed. No new incursions were reported for the natural environment.

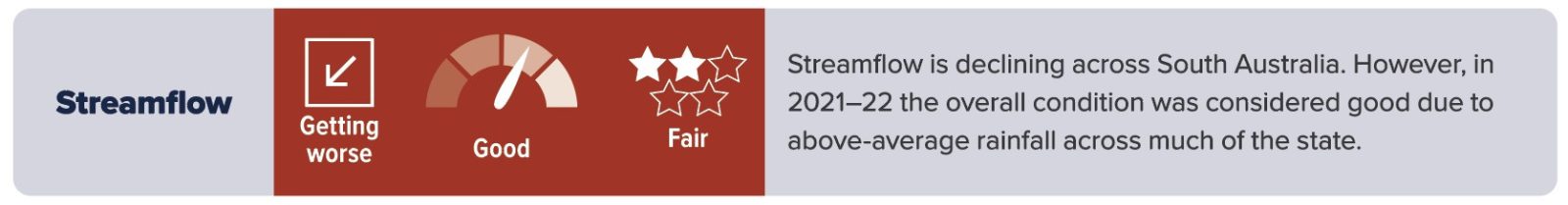

Streamflow and Flow Regime

The condition of streamflow (surface water quantity) is considered to be good in South Australia driven by the above average rainfall that occurred across much of the state in 2022. However, since 1986, the trend in streamflow has shown a decline for each landscape region, with the exception of Alinytjara Wilurara and Green Adelaide, for which the trends are unknown.

The overall flow regime condition (number of flowing days) is generally considered to be good in South Australia, although is variable across the landscape regions. However, the trend for flow regime for surface water is showing a decline across every landscape region, except for Alinytjara Wilurara and Green Adelaide, for which the trends are unknown.

The flow regime of a river is one of the main drivers of aquatic ecosystem condition, and increased flowing days enable more flora and fauna to complete life cycles and support biodiversity and improved water quality. Flow regimes are influenced by rainfall and groundwater infiltration via springs into rivers and can be impacted by climate change, capture of runoff into dams and extraction of groundwater.