- Home

- Environmental Themes

- Sea

- State of Our Sea

- Habitats and Ecosystems

Habitats and Ecosystems

Dunes and Beaches

Adelaide’s beaches are the most visited public land in South Australia. South Australia has some of the best beaches in Australia. In 2023, Stokes Bay on Kangaroo Island was crowned the best of 11,671 beaches. In 2022, Flaherty’s Beach on Yorke Peninsula ranked fourth and Emu Bay on Kangaroo Island ranked sixteenth. Beaches are popular for swimming, surfing, fishing, camping, boating, tourism and 4WDing. They also provide habitat for coastal species such as Hooded Plovers, a threatened beach-nesting shorebird, which can be impacted by these activities.

Work is being undertaken by the Department for Environment and Water and local councils to protect and restore sand on Adelaide’s beaches. In 2017, a coastal processes modelling study was undertaken, which found that sand loss at West Beach was significant and erosion will continue around West Beach and Henley Beach south and progressively move north. A beach management review is currently being undertaken by government to identify options for the long-term management of Adelaide’s beaches. A sustainable approach for managing sand movement that protects our beaches along the entire Adelaide coastline needs to be considered.

Dunes play an important role in supporting coastal biodiversity and protecting our coastlines from erosion and storm surges. The vegetation in dunes helps stabilise sand, thereby preventing it from being carried away by wind and water. In addition, it provides habitat for birds, reptiles, mammals and insects. The protection of vegetation within dunes is, therefore, critical for maintaining these ecosystems and protecting our shoreline.

Many of our coastal camp sites are located within dunes, particularly along Yorke and Eyre peninsulas. Impacts to dunes and beaches from camping and 4WDing were raised during regional consultation undertaken by the EPA for the SOER. The Eyre Peninsula Landscape Board has advised that since the implementation of the Eyes on Eyre project, local councils have reported better compliance from campers.

The Coast Protection Board was formed in 1972 under the Coast Protection Act 1972 to protect and restore South Australia’s coastline. DEW and Landscape Boards are also involved in undertaking research and managing our coast.

Estuaries

Estuaries are where fresh water from the land mixes with tidal waters from the oceans. Estuaries provide essential habitat for marine organisms and are important areas for some of South Australia’s commercial and recreational fisheries. In 2009, 102 estuaries were mapped in South Australia.

There is very limited information on the trend and condition of South Australian estuaries apart from the Coorong, which is a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance. A project has recently been completed by the Goyder Institute on science advice for restoring the ecological character of the South Lagoon of the Coorong.

The EPA is currently undertaking a scientific assessment to understand the current state of the Port Adelaide waterways particularly with respect to the reduction of pollution discharges that have occurred with the closure of Penrice Holdings and improvements made at Bolivar Wastewater Treatment Plant. As of 2019, it was found that 83% of the water quality objectives identified in the Port River Water Quality Improvement Plan had been met.

Check out

Mangroves and Saltmarshes

Mangroves are generally found along low-energy, fine-sediment shorelines and there are significant stands near Ceduna on the West Coast, Franklin Harbour near Cowell, the northern ends of the two gulfs near Port Pirie, and between Port Adelaide and the Light River delta. They are highly productive nurseries, feeding and breeding areas for fish and crustaceans, habitat for seabirds and waterbirds, and form part of the coastal food chains. They also trap sediments and provide an important sink for nutrients, blue carbon and physical protection against storms.

In contrast to mangroves, the species richness of tidal saltmarshes increases with latitude. Where saltmarsh and mangrove distribution overlap, they usually form adjacent, connected communities in the intertidal zone. These highly productive tidal environments provide key habitat for resident and migratory shorebirds, feeding and refuge areas for fish, and rare or endangered plants such as Centrolepis, Wilsonia and Tecticornia.

Intertidal and supratidal saltmarshes are an essential hydrological buffer between seaward mangroves and terrestrial ecosystems, regulating salinity and water velocity, and decreasing the suspended sediment load and nutrients entering the marine environment.

Saltmarshes are recognised as one of the most efficient natural systems for capturing and storing carbon. In 2021, 275.6 million tonnes of carbon (MtC) were stored in saltmarsh and 10.1 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent were sequestered annually (tCO2e yr–1) in Australia.

The trend and condition of coastal mangrove and saltmarsh percentage cover is unknown due to the change in satellite technologies used to undertake measurements. It is known that there has been a loss of mangrove cover due to clearing for coastal urban developments, pollution discharges and oil spills. In 2020, the percentage cover of mangroves was 0.014% statewide (based on an estimated extent of 14,200 ha) and saltmarsh 0.019% statewide (based on an estimated extent of 18,700 ha), with the Northern and Yorke and Eyre Peninsula landscape regions supporting the most coverage.

However, a report by Foster et al (2019) that discusses an assessment of coastal carbon opportunities, looks at changes in the distribution of mangrove and saltmarsh across South Australia, from 1987 to 2015, and indicates that there had been a net increase in the area of both saltmarsh and mangrove ecosystems during that period, with saltmarsh increasing by 9% equating to 16 km2 and mangroves by 5% equating to 7.9 km2.

In 2020, vegetation dieback, which included 9 hectares of mangroves and 10 hectares of saltmarsh, was noted within the Adelaide International Bird Sanctuary National Park—Winaityinaityi Pangkara at St Kilda. Mapping was undertaken in 2021 to identify the extent of dieback that had occurred in the sanctuary. Investigations and monitoring are being undertaken and coordinated by the DEM, DEW and EPA to prevent further impact and promote recovery of the affected areas. Monitoring results are provided on the DEM website.

Seagrass

There are 11 recorded species of seagrass in South Australian coastal waters. In South Australia, seagrass is protected under the Native Vegetation Act 1991 administered by the Department for Environment and Water. In addition, seagrass is also protected from pollution under the Environment Protection (Water Quality) Policy 2015 administered by the EPA.

Seagrass habitats are extremely important for the following reasons:

- 1 m2 of seagrass generates around 10 litres net of oxygen each day.

- Seagrass leaves absorb nutrients and slow the flow of water, thereby capturing sand and silt. Their roots also trap and stabilise sediment, therefore minimising erosion and improving water clarity and quality.

- Seagrass supports biodiversity and provides nursery habitats, and feeding and refuge sites for marine species and, therefore, supports biodiversity. This also includes species that are commercially fished, such as marine scalefish, Blue Swimmer Crabs, Southern Calamari and Western King Prawns. Many of these species are also recreationally fished, which supports tourism in regional areas.

- Seagrass stabilises the seabed and minimises coastal erosion that can be caused by waves and currents.

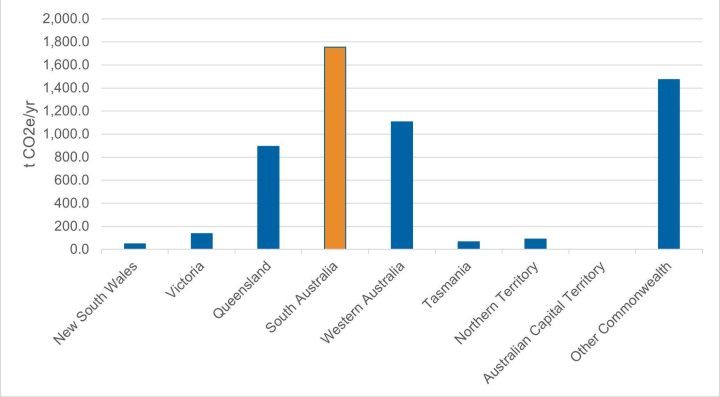

Seagrass stores up to twice as much carbon as terrestrial forests and, therefore, plays an important role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. As of June 2021, it was estimated that between 289 and 341 million tonnes of carbon (MtC) were stored in known seagrass meadows in Australia. Of all the states and territories, South Australia had the highest level of carbon stored in seagrass of 74 MtC, with 89% of this being stored in seagrass located within Spencer Gulf and Gulf St Vincent. National carbon sequestration estimates for seagrass for August 2022 ranged between 4.9 and 5.6 Mt CO2e/yr (or the equivalent to emissions of 1.6 to 1.9 million cars). Seagrass in South Australia provided the highest carbon sequestration services (1.75 Mt CO2e/yr).

One hectare of seagrass is estimated to be worth more than $26,000 per year based on the ecosystem services they provide, making seagrass one of the most valuable ecosystems in the world. South Australia is undertaking a large-scale seagrass restoration project to help bring back seagrass along the metropolitan coastline. A report was undertaken by SARDI to help inform options for seagrass restoration.

The coverage of seagrass (Posidonia and Amphibolis) across the South Australian coastline is considered to be stable. It appears to be increasing in the Green Adelaide region and declining around Kangaroo Island, predominantly due to observed loss in Nepean Bay. The Cygnet River catchment runoff has been linked to extensive loss of seagrass in this area.

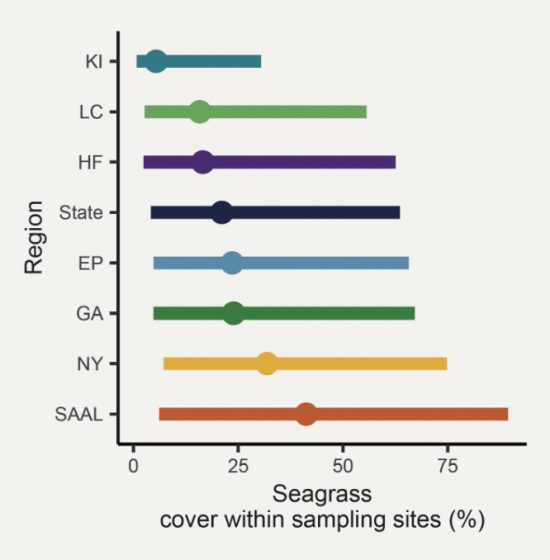

At a regional scale, estimates of seagrass cover within sampling sites varied between and within landscape regions.

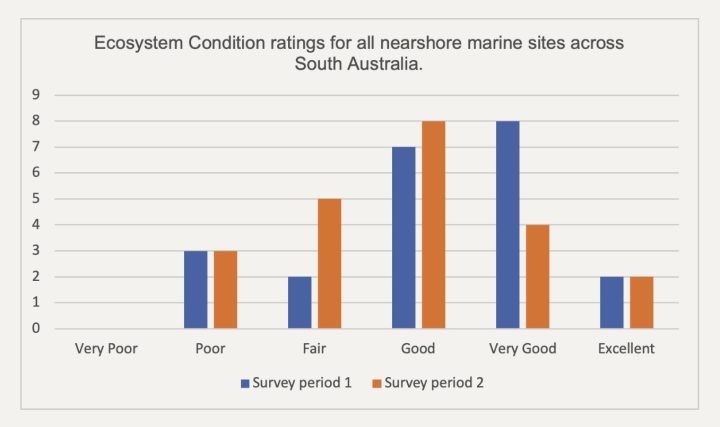

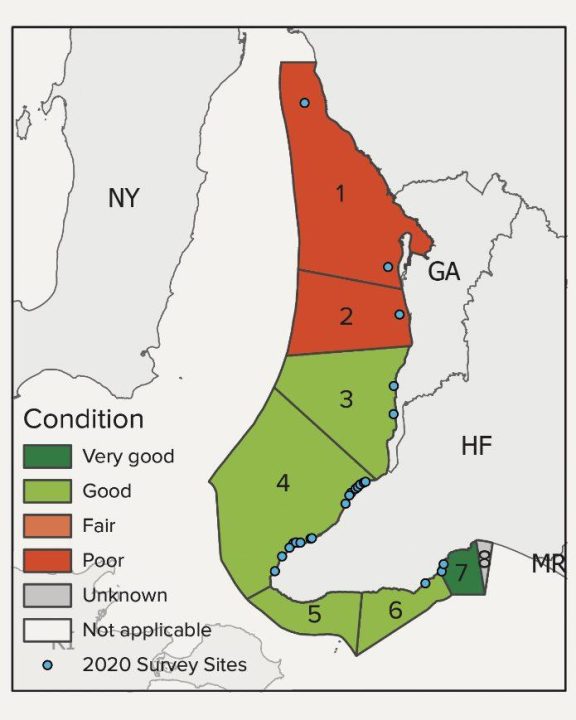

The EPA monitors the health of the marine environment via its Aquatic Ecosystem Condition Reporting, which includes other parameters besides vegetation cover to measure ecosystem health. One region is surveyed each year, which is repeated every five years. Ecosystem condition is variable across the state with some regions improving between survey periods and others declining in condition. The areas in best condition are generally located away from human interference and coastal development, where they are least exposed to nutrient enrichment from activities such as wastewater and stormwater discharges, sea cage aquaculture and dredging. Particularly healthy sites are located along the far west coast and limestone coast of South Australia.

Along the Adelaide metropolitan coastline, over the last 70 years, the cumulative impact of discharges has contributed to the degradation of the nearshore environment with the loss of over 6,000 hectares of seagrass and degradation of rocky reefs . Once lost, seagrass meadows do not easily recover. There has been some seagrass regrowth through improvements in water quality from the implementation of the Adelaide Coastal Waters Quality Improvement Plan. In addition, reduced nutrient inputs and enhanced management of wastewater from Bolivar wastewater treatment works and the closure of Penrice soda ash plant in 2014 have also likely resulted in seagrass growth.

However ecosystem condition is still being impacted by nutrients and sediments discharged from various sources including stormwater and wastewater treatment plants. Reducing nutrient and sediment loads by improving reuse of stormwater and wastewater and better integration of water sensitive urban design into urban planning would help reduce pollutant loads that are being discharged into the marine environment.

Further reading

- Towards a consolidated and open-science framework for restoration monitoring and Inclusion of sediment processes in restoration strategies for Australian seagrass ecosystems – National Environmental Science Program (Marine and Coastal).

Subtidal and Intertidal Reefs

Reef habitats are important for a number of species caught by commercial and recreational fishers, including Nannygai, abalone and the Southern Rock Lobster.

Reefs support a diverse range of macroalgae usually in areas of high-wave exposure and cold-water oceanic upwelling, for example, the South East, southern Eyre Peninsula and southwestern Yorke Peninsula. Reefs also exist in intertidal areas.

The majority of the 1,200 recorded species of macroalgae in South Australia are endemic and their diversity is amongst the highest in the world. This is largely due to the length of the southern facing rocky coastline (the longest east-west, temperate coastline in the world) and the long period of geological isolation.

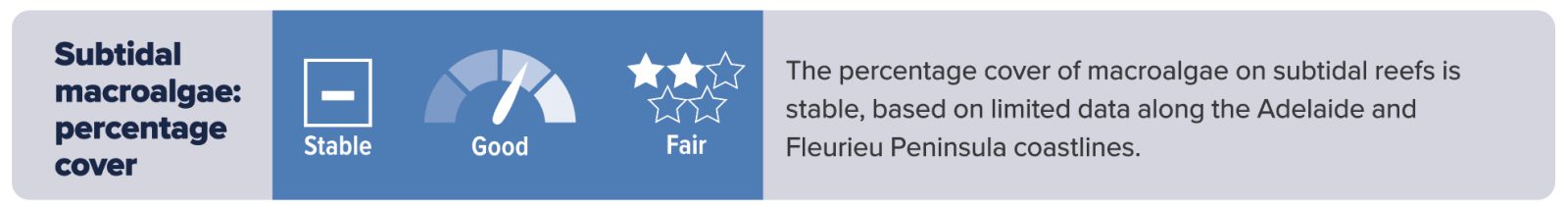

Macroalgal percentage cover on subtidal reefs along the Adelaide and Fleurieu Peninsula coastlines are generally in good condition, with assessments indicating there is a north–south gradient of increasing cover because of natural differences in the environment, as well as increased pollution levels from urban development due to stormwater runoff and wastewater treatment plant discharges. The statewide trend in macroalgal percentage cover has been assessed as stable across these regions. However, the condition and trend of other regions are unknown.

Sandy Bottoms

Sandy habitats dominate South Australia’s coastline, occupying about 59% of the coastline, and are prevalent in all regions. They provide important ecosystem services and contain a rich community of infauna and epifauna, which are important food sources for other benthic animals and help maintain the stability of the sea floor. The composition of epifauna and infauna provides an indication of the health of the benthic environment and has been used as an indicator for environmental monitoring of finfish and tuna farms near Port Lincoln and the Adelaide desalination plant.