- Home

- Environmental Themes

- Liveability

- Stormwater

Stormwater

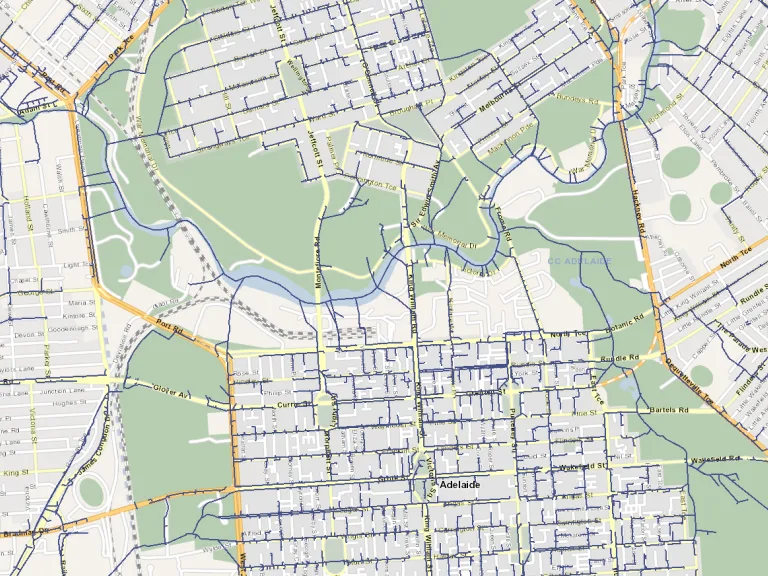

The stormwater drainage system in Adelaide is extensive as illustrated in this small portion of the network around the northern region of the CBD.

Management

Stormwater is primarily managed by local government. The Stormwater Management Authority (SMA) is a state government body that acts as a stormwater planning and prioritisation body for South Australia. The SMA promotes the development of integrated Stormwater Management Plans (SMPs) by local government and administers the Stormwater Management Funds. Priority areas for SMPs was released by the SMA in 2022.

In built-up areas, stormwater is carried away by a series of pipes, known as the stormwater drainage network, to our natural waterbodies, including creeks, rivers and the sea. In some areas such as Mount Gambier, urban stormwater is discharged directly to the underground aquifer via EPA licensed drainage bores. Some will also permeate through soils into groundwater if the conditions allow.

Urban areas have more built-up and covered impermeable surfaces and less green space, which leads to higher stormwater runoff and potential localised flooding. This may impact property, businesses and the natural environment. It can also pick up pollutants such as litter, organic matter, oils, plastics, toxicants and sediments along its journey down stormwater drains, which is then discharged untreated, except where there are gross pollutant traps, into our creeks, rivers and the sea. This may impact native animals and plants that live in these habitats and our use of these waters. Stormwater pollution is usually referred to as diffuse pollution because it does not come from one readily identifiable source, but rather from a range of sources over a large area that cumulatively have significant environmental impacts.

Water sensitive urban design has been applied at a number of locations. Incorporating water sensitive design into new developments provides multiple benefits, including reducing stormwater runoff and, consequently, the risk of flooding. It also helps retain water for greening, thereby helping to mitigate the urban heat island effect. Inclusion of rain gardens, wetlands and retention/detention ponds in new developments and redevelopments treats stormwater to improve water quality, and can enhance liveability by providing blue-green spaces.

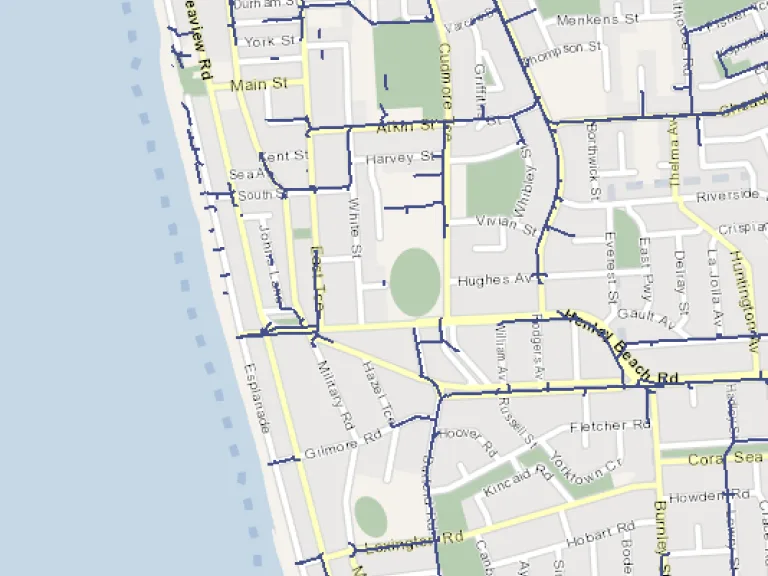

The EPA’s aquatic ecosystem condition monitoring has demonstrated that waterways located in urban environments where stormwater runoff occurs are generally in poor condition. Stormwater runoff has also contributed to seagrass loss that has been experienced along the Adelaide coastline. The EPA coordinated the Catchment to Coast program to further investigate, and action, water quality improvement across metropolitan Adelaide. Some progress has been made, but more needs to be done to reduce stormwater flows and, consequently, nutrient and sediment loads into inland and marine waters.

A Stormwater Data Audit Report was commissioned by the EPA in 2015, which included an assessment of quality and quantity of stormwater being discharged into the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study area. The 2015 audit indicated that the total suspended solids discharged between 2009 and 2014 was 24,800 tonnes, with an average of 4,140 tonnes per year. The significant catchment contributions to this quantity were the Torrens River (36%), Gawler River (13%), Onkaparinga River (7%) and Barker Inlet Wetland Outlet #1 (15%). Quantity and quality of stormwater can vary as a result of many factors, including duration between and intensity of rain events, land use (including building density, vegetation cover and street pollution/cleanliness) and strategies that have been implemented to improve the quality of stormwater, for example, gross pollutant traps and rain gardens. It is suggested this audit be repeated at least every ten years to identify if the implementation of WSUD has been effective in improving water quality and reducing sediment loads in stormwater.

Stormwater is also a resource and can be diverted from the stormwater drainage system and used for other purposes such as irrigation, household use and industry. This can be done by installing rainwater tanks, retention basins, rain gardens or managed aquifer recharge. Benefits of this include:

- reducing pressure on water supply

- reducing risk of flooding during rainfall

- expanding green spaces and gardens.

The 2018 State of the Environment Report stated that the aim was to harvest 35 GL of stormwater by 2025. According to the Water Security Statement 2022, only 4.4 GL of a total of 140 GL of stormwater and water from urban watercourses across urban Adelaide is currently reused.

The Goyder Institute for Water Research undertook an assessment into the management of stormwater within our urban environment. The report provided a number of recommendations for stormwater management, including reviewing governance, implementing strategies that recognise the importance and reuse of stormwater and implementing programs to monitor and improve the water quality of stormwater.

Coordination and implementation of best practice for the management of stormwater runoff is still required to manage and improve the quality of stormwater that flows into surface waters and the marine environment, and may have other added benefits such as providing water for greening and helping cool our urban centres. This could be facilitated by incorporating WSUD requirements into planning policy for new developments and implementing provisions to ensure that water sensitive design infrastructure is used when existing stormwater infrastructure is replaced.

Responding to Pressures

Pressures

- Increased stormwater runoff from:

- extreme rainfall events

- urban infill and sprawl

- reduced green space

- lack of impermeable surfaces.

- Pollution picked up in stormwater, for example, leaves, oils, grease, litter, construction waste, sediments and tyre shreds.

Impacts

- Less water reaching groundwater, which can impact water supply for groundwater users.

- Greater flows of potentially polluted water into our natural waters, which may impact plants and animals and cause erosion of riverbanks and impact beaches.

- Localised flooding that may impact property and businesses.

- Increase in nutrients into waters, which may result in algal blooms and impact aquatic ecosystems.

- Discharge of sediments into aquatic environments that smothers plants and animals and reduces light reaching seagrass.

- Toxic substances picked up in stormwater, such as tyre shreds, oils, grease and other substances may impact plants, animals and water quality.

- Reduction in oxygen for aquatic plants and animals resulting from decomposition of organic matter in stormwater or from algal blooms due to added nutrients from stormwater.

- Flow blockages from the buildup of debris and sediment increasing the occurrence of localised flooding.

Responses

- Water Sensitive SA provides a number of support tools and options to improve and manage stormwater quality through water sensitive urban design. A number of projects have been implemented in South Australia including the completion of Breakout Creek that improves ecosystem health and water quality of the River Torrens before it reaches the marine environment.

- The SMA has released new stormwater management planning priorities for South Australia that look at flooding and drainage risks, water quality risks, stormwater reuse potential, climate change adaptation, development pressure and adequacy of existing plans for metropolitan Adelaide and 60 regional cities and towns.

- Gross pollutant traps are used to capture rubbish and other debris before it reaches our waterways. According to Green Adelaide, in the Torrens and Patawalonga catchments, the equivalent of around two Olympic-sized swimming pools of debris was captured during 2022–23. Across metropolitan Adelaide, around 2,300 to 3,300 tonnes of material is captured per year in gross pollutant traps.

- During high rainfall events in summer, the EPA may issue a ‘beach alert’ advising swimmers to not swim within a specified region for a period of time after high stormwater flows with regard to water quality.

- The discharge or deposit of a pollutant into stormwater is prohibited under EPA legislation and the Local Nuisance and Litter control Act 2016. This includes water from washing boats and cars, water from swimming pools, construction waste and discharging listed pollutants.

- Some councils have incorporated wetlands and rain gardens to assist in managing polluted stormwater.

- Under EPA legislation and the Local Nuisance and Litter Control Act 2016 every person has an obligation to prevent pollution entering the stormwater system.

- Development approvals can include requirements to develop and effectively implement a stormwater management plan to address risks to stormwater during construction and beyond (eg, sediment-laden runoff).

Stormwater Opportunities

- Greater development-industry compliance with stormwater management requirements, driven either by industry self-regulation or stronger compliance action by planning authorities (often local government) to ensure development conditions are being met during construction.

- Inclusion of rain gardens, wetlands and/or retention/detention ponds in new developments and redevelopments that treat stormwater and enhance liveability by providing blue-green spaces. Water sensitive design that retains runoff has multiple benefits, including more natural flow regimes and retention of water for greening to help mitigate the urban heat island effect.

- Incentives to install larger rainwater tanks to capture rainfall, particularly in new builds, and ensure that rainwater is plumbed within households and used to maintain adequate detention capacity.

- Installation of permeable paving (for example, for carparks and footpaths) to reduce stormwater runoff and enable the recharge of groundwater.

- Expand the use of rain gardens and retention/detention ponds to regulate and treat stormwater.

- Incorporate WSUD into planning policy for new developments that includes the reuse of stormwater and considers flood management, and introduce provisions to ensure that water sensitive design infrastructure is used when existing stormwater infrastructure is replaced. This needs to consider capacity during extreme rainfall events.

- Undertake monitoring to identify whether the implementation of water sensitive design is effective. This may include repeating an audit of stormwater water quality and quantity at least every ten years to identify whether there have been any improvements to water quality as a result of implementation of WSUD.

Further Reading

- Options Analysis: Costs and Benefits of Stormwater Management Options for Minor Infill Development in the Planning and Design Code 2020 – A report by BDO EconSearch to identify cost-effective ways to balance stormwater management and urban infill.

- Future urban water management options for vibrant and resilient Adelaide (Goyder Institute for Water Research) – An assessment of the options for the future management of urban water and waterways to support a vibrant Adelaide.

- Urban Waters Directions Statement December 2021 – A report by DEW that outlines strategies for urban water management.

- Stormwater Management Planning Priorities for South Australia 2022 - Identifies priorities by the Stormwater Management Authority to guide the ongoing development and updating of stormwater management plans.

- Water Sensitive Urban Design Projects in South Australia – An interactive map that identifies location and types of WSUD projects.

- Adelaide Coastal Water Study: Stormwater Data Audit Report 2015 – Assessment of quality and quantity monitoring of stormwater being discharged into the Adelaide Coastal Waters Study area.