- Home

- Environmental Themes

- Sea

- Pressures and Responses

- Pollution

Pollution

Nutrients and Sediments

Nutrients and sediments are discharged or emitted into the marine environment via groundwater or runoff from various sources including:

- stormwater runoff

- industrial discharges

- agriculture

- wastewater treatment plants

- desalination plants

- aquaculture

- dredging.

Leaking septic tanks in coastal locations are likely to be contributing to nutrient loads within the marine environment as a result of:

- septic tank leakage that may be reaching the marine environment through groundwater in the South East

- failing and/or high density of on-site wastewater treatment (septic) systems in some coastal towns along the Eyre and Yorke peninsulas that may be creating leakage into the marine environment

- overflowing septic systems that might be releasing nutrients into nearshore marine waters through shallow subsurface water or occasional overland flows.

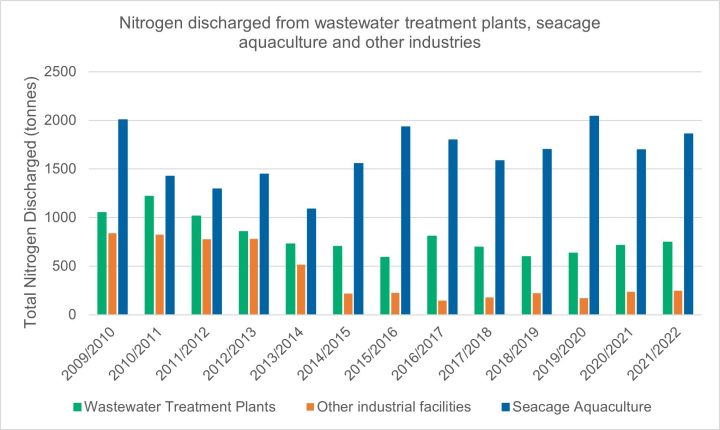

- Sea-cage aquaculture and wastewater treatment plants are the highest emitters of anthropogenic nitrogen to the marine aquatic environment.

Impacts

- Increased risk of harmful algal blooms due to increased nutrients, which may result in aquatic animal mortalities including:

- declines in oxygen levels caused by algal blooms that may impact aquatic animals and cause fish kills

- impacts to our seafood industry from harmful algae, in particular shellfish such as oysters and mussels that would become unsafe to eat.

- Epiphytic algal growth and increased turbidity smothers seagrass and reduces light availability, which can cause seagrass loss. Epiphytes have been noted in regions that are subject to high nutrient and sediment loads from various sources, and potentially coupled with low flushing rates, for example, lower Eyre Peninsula near Port Lincoln and Coffin Bay, Nepean Bay on Kangaroo Island, northern Adelaide beaches and Streaky Bay.

- Impacts to swimmers and triggering of beach alerts due to poor water quality (cloudy water reducing visibility of obstacles etc).

Responses

- Some industries who discharge nitrogen into the marine environment are required to report their emissions to the National Pollutant Inventory (NPI) to help further understanding of environmental risks and cumulative impacts from multiple sources of nutrient inputs. Some industries are not required to report, eg sea-cage aquaculture.

- EPA licences are based on a 'polluter-pays' principle, where the cost of a licence reflects the amount and type of pollutants that are discharged into the marine environment. Dredging, wastewater treatment plants, desalination plants and other industries that discharge pollutants or have the potential to impact the marine environment are licensed by the EPA.

- Monitoring is undertaken by industry to identify and manage impacts. This includes the Adelaide Desalination Plant and wastewater treatment plants, Whyalla Steelworks and dredging:

- There have been no significant impacts noted from monitoring undertaken for the Adelaide Desalination Plant, wastewater treatment systems and Whyalla Steelworks.

- The Whyalla Steelworks has monitored a 5-fold increase in seagrass since 1990 and up to 10-fold in some areas due to system improvements to reduce the level of nitrogen discharge.

- The EPA is working with dredgers to improve practices that will reduce the release of sediments and nutrients into the environment. One example is the Outer Harbor channel widening project, which resulted in significant seagrass loss due to extensive sediment plumes when dredging occurred in 2005–06. No significant impacts to seagrass have been recorded for the 2019 dredge campaign due to major changes in dredging practices that reduced and monitored sediment plumes and turbidity.

- Monitoring is also undertaken by the aquaculture industry to identify and manage impacts. The outcomes of this monitoring is reported in PIRSA’s Zoning In: South Australian Aquaculture Report 2015–16, 2021, 2022 and 2023. The 2015–19 environmental monitoring program for finfish and tuna indicated that aquaculture may be having some effect on the ecosystem. Monitoring over the 2019–23 period was expanded to further investigate these effects. This report has not yet been published. Additional environmental monitoring is also undertaken for Yellowtail Kingfish. The recent review of the Aquaculture (Zones – Lower Eyre Peninsula) Policy 2023 also used a hydrodynamic and biogeochemical model developed by SARDI to inform the identification of flushing zones and more sustainable carrying capacities for fish biomass that will facilitate the flushing of nutrients from farming zones. The amended policy also supports the growth of Integrated Multitrophic Aquaculture. A FRDC project has recently been approved to identify opportunities for the farming of multispecies to provide nutrient offsets, carbon uptake and ecosystem services (FRDC Project 2023–051).

- Aquawatch Australia is being coordinated by CSIRO to facilitate real–time monitoring of water quality that will support better water quality management and provide an early warning of harmful algal blooms.

- Rehabilitation of habitat that has been lost due to discharges, for example, seagrass recovery study with Whyalla Steelworks and the Seeds for Snapper project to help restore seagrass meadows around metropolitan Adelaide and the Fleurieu Peninsula.

- Shellfish reefs have been constructed to help filter sea water. These reefs also provide other benefits to the marine environment. Windara Reef, adjacent to Ardrossan, was the first shellfish reef established in South Australia, and is the largest restored reef in the Southern Hemisphere at 20 hectares. There are now three other reefs established at O’Sullivan Beach, Glenelg and Kangaroo Island.

- Implementation of water sensitive urban design is being undertaken by many councils to improve water quality and reduce stormwater runoff into the marine environment, and treat water prior to it entering the marine environment, for example, River Torrens Breakout Creek development.

- The Goyder Project is being carried out to help inform a decision framework for selecting stormwater management interventions to reduce fine sediments and improve coastal water quality.

- Installation of community wastewater management systems (CWMS) to reduce operation of septic tanks. There are currently 175 CWMS located across 50 councils.

- Wastewater treatment plants are recycling some wastewater to reduce the volume of discharges into the marine environment.

- The South Australian Shellfish Quality Assurance Program (SASQAP) monitors water quality for toxic algae and other parameters in shellfish harvesting areas of the state to ensure shellfish are safe to eat. Restrictions are placed on harvesting shellfish for human consumption if necessary.

- Many businesses are seeking independent environmental certification for their business, to demonstrate environmental compliance and implementation of environmental best practices, and to strengthen their marketing efforts.

Opportunities

- Better management of stormwater and wastewater, including increasing the capacity to reuse and recycle water to further reduce discharges into the marine environment. This was suggested on numerous occasions during the EPA’s regional consultation for the SOER.

- Improve the implementation of measures to reduce pollution inputs into creeks, rivers and stormwater that flow into the marine environment.

- Introduce a more coordinated approach to assess and manage the impacts of cumulative nutrient inputs on marine ecosystem health, including further investigation into the source and fate of nutrients in regions where seagrass impacts are being observed.

- Facilitate the expansion of integrated multitrophic aquaculture, which partners the farming of finfish species that emit nutrients with species that assimilate nutrients such as filter–feeding shellfish and algae.

- Encourage the movement of Yellowtail Kingfish and Southern Bluefin Tuna farms further offshore into higher flushed areas that have been identified by modelling undertaken by SARDI.

Waste

Pressures

- Waste from commercial and recreational fishing and aquaculture, particularly on Eyre Peninsula, which supports an extensive seafood industry.

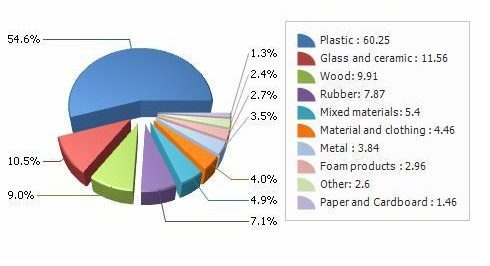

- Marine plastic pollution including microplastics. Main sources of plastic pollution appear to be from litter, fishing waste, wastewater treatment plants, tyre dust and stormwater.

- Waste from campers and beach goers, including bottles, cans, coffee cups, toilet paper and broken camping equipment.

Impacts

- Entanglements of birds and mammals from nets, ropes, fishing line and other waste.

- Microplastics can affect ecosystems, biodiversity and, potentially, human health.

- Impacts to the amenity of the coastal environment.

Responses

- A report was undertaken by the National Environmental Science Program (NESP) in 2022 to identify knowledge gaps and potential solutions to support the development of strategies to manage microplastics in coastal environments.

- South Australia is promoting the circular economy and managing the usage of single-use plastics to minimise the number of plastics in the environment.

- Research is being undertaken by the CSIRO, NESP and FRDC to further understand sources and impacts of plastics in the marine environment to help inform management responses and policy development.

- Aquaculture Regulations 2016 administered by PIRSA require licensees to recover waste as soon as practicable.

- A recycling facility has been established on Eyre Peninsula to support recovery of fishing and aquaculture waste.

- The aquaculture industry on Eyre Peninsula has implemented adopt a beach program. Beach programs are coordinated by the Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association and are undertaken four times a year. While some waste is attributed to the aquaculture industry, other waste also originates from other sources, including commercial and recreational fishing, land–based operations, commercial shipping and the general public.

- Beach clean-up days are undertaken in other areas to facilitate the collection of waste from our beaches. Green Adelaide also manages a marine debris program to collect information on the composition of litter found in our oceans.

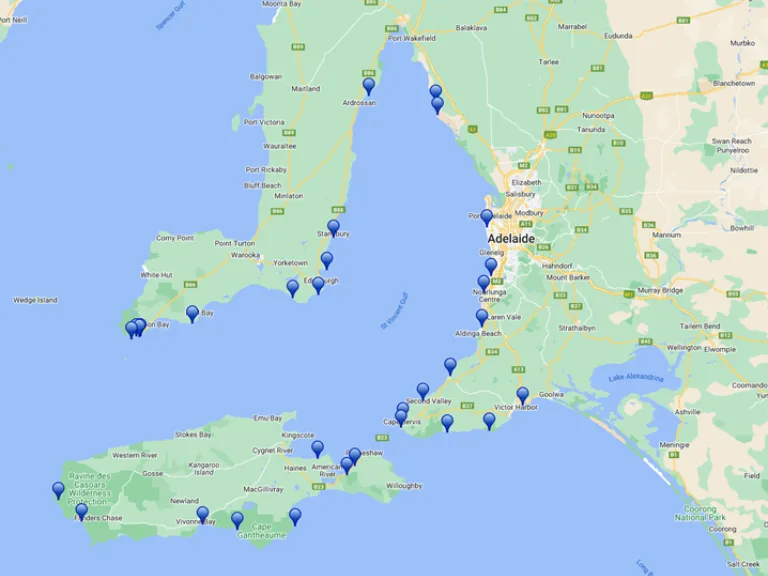

Composition and kilograms of items collected between September and December 2022 along the coastline highlighted in the map. Plastics comprised the highest composition (87.9%) and greatest amount of waste (59.6 kgs) (Green Adelaide Marine Debris Program)

Opportunities

- Innovations in recycling of plastics (especially soft plastics)

- Further identify sources and pathways of plastic pollution to the environment.

- More frequent coordinated beach clean–up events across South Australia’s beaches. For example, Victoria’s Beach Patrol.

Toxicants

Pressures

- Chemicals of emerging concern, for example, antimicrobials, per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), plastics, brine and pharmaceutical products.

- Toxicants used or emitted by human activities or industries, for example, the Port Pirie smelter, dredging in high-risk environments, antifoulant use on marine equipment and vessels, pesticide and herbicide use, and desalination plants. These toxicants can reach the marine environment via stormwater, groundwater, industry discharges, and potentially from leaking septics in coastal locations.

- Oil spills from marine infrastructure, vessels or marine exploration and drilling (it should be noted that marine exploration and drilling activities are undertaken in Commonwealth waters and are, therefore, not under the legislative control of the South Australian Government).

- Antibiotics used in the aquaculture industry to protect fish health.

Impacts

- Accumulation of toxicants in sediments and impacts on aquatic animals and plants potentially affecting biodiversity, for example, the Port Pirie smelter.

- Anti-microbial resistance in bacteria leading to impacts on biodiversity and aquatic industries such as fishing and aquaculture.

- Contamination of aquatic species fished for human consumption.

- Impacts on seagrass, aquatic vegetation and organisms from toxicants, for example, the St Kilda Mangroves that has been affected by salty water from the Dry Creek Salt Fields.

- Oil spills introduce toxic material into the food chain, degrade beaches and can smother marine organisms.

Responses

- A Subcommittee for Contaminants of Emerging Concern was established under the Heads of EPAs in 2021 to facilitate a coordinated approach across Australia to address emerging issues.

- One Health Master Action Plan provides guidance on implementing Australia's National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy: 2020 and Beyond (the 2020 Strategy). In March 2020, the Australian Government released the 2020 Strategy to combat the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

- Fisheries Research Development Corporation is actively involved in CRC SAAFE (Solving Antimicrobial Resistance in Agribusiness, Food and Environments) to help identify and implement best practice to mitigate antimicrobial resistance in the seafood industry and aquatic environment.

- The PFAS National Environmental Management Plan (PFAS NEMP) provides nationally agreed guidance and standards on the investigation, assessment and management of PFAS wastes and contamination in the environment, including prevention of the spread of contamination.

- Antibiotic use is regulated by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority through minor use permits and registrations. In South Australia, off–label use of antibiotics in aquaculture is also regulated by PIRSA under the Aquaculture Regulations 2016 in consultation with the EPA.

- Assessment, approval and regulation of antifoulant use through labelling is undertaken by the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority.

- Reporting of oil spills and implementation of the South Australian Marine Spill Contingency Plan.

- Licence conditions and monitoring requirements are required for industry to manage and monitor risks from toxicants and minimise the potential for environmental harm. This includes impacts to environmental values such as fisheries and aquaculture.

- Monitoring undertaken by industry to detect the occurrence of chemicals in the marine environment. Fishing closures may be implemented by PIRSA if harmful levels of chemicals are detected, for example, Port Pirie.

- Some industries that emit chemicals to the environment need to report their emissions to the National Pollutant Inventory (NPI).

Opportunities

- Currently, there is limited data about the environmental occurrence of chemicals of emerging concern. Therefore, until more is known, risks resulting from these chemicals should be considered as high.

- Further investigation into sources, interactions and accumulation of chemicals in the environment.

Further reading

- Marine and Coastal National Environmental Science Program – Microplastics in southeastern Australia coastal waters: synthesising current data and identifying key knowledge gaps for the management of plastic pollution.

- CSIRO marine pollution – Sources distribution and fate of plastic pollution in the marine environment.

- Shellfish reefs in Australia – Information on the construction of shellfish reefs and the benefits they provide.

- Marine plastics: impacts and policy responses – Information from FRDC regarding the impacts of plastic pollution in the aquatic environment.

- One Health Master Action Plan for Australia’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy – 2020 and beyond – This plan provides national focus areas for each of the One Health sectors to implement the strategy and guidance for stakeholders to develop their own action plans to combat AMR.