Published:

Author:

Malleefowl Leipoa ocellata, known as nganamara in Pitjantjatjara, are stocky ground-dwelling birds about the size of a chicken.

They are best known for their large nest mounds, which can be more than 1 metre high and several metres across. Their mounds are built on a base of organic material that generates heat as it breaks down. The covering of sand on top provides insulation and the birds adjust it diligently to keep the temperature just right for the developing eggs inside.

Nationally, the nganamara is listed as Vulnerable under the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Previously found throughout much of semi-arid to arid Australia, their range and population are severely reduced. This decline is mostly attributed to land clearing for farming. In addition, the species is at threat from various introduced species such as the cat and red fox.

In dry years many mounds remain dormant as rain is needed to support composting of the leaf litter which creates the warmth vital to successful incubation of the eggs. This makes them susceptible to further risk from climate change.

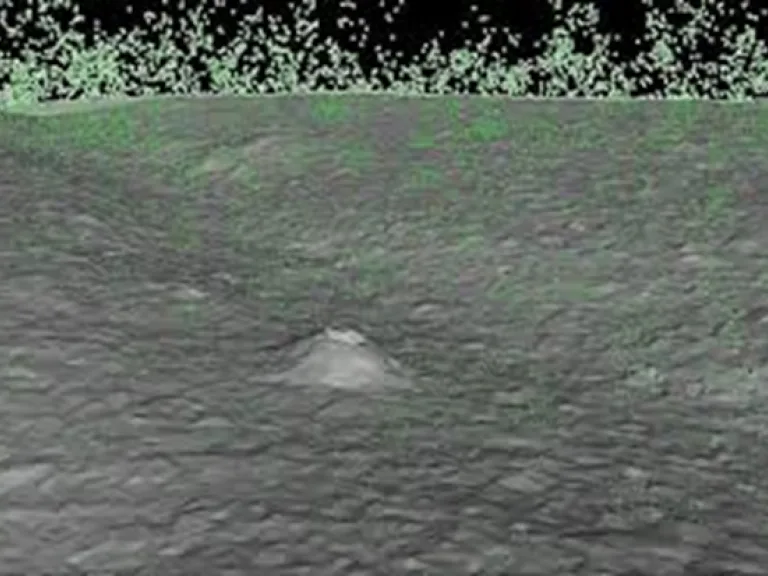

The Alinytjara Wilurara Landscape Board (AWLB) has monitored malleefowl populations since 2007. Initial surveys were undertaken on foot, based on analysis of data that dated back to 1983. From 2018, AWLB surveyed more than 35,000 hectares of the Great Victoria Desert using airborne LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) and discovered 36 previously unknown Malleefowl mounds, with a third of these in active use. For this arid landscape that is a high number of nest sites, with an active percentage much higher than the national average. The LiDAR surveys added significant new information to AW’s long-term datasets.

AWLB gathers data on the Malleefowl habitat, including feral predator numbers, impacts of large feral herbivores, and distribution of other vulnerable species. AWLB’s fauna surveys, conducted as part of this project, have extended the known range of the elusive Sandhill Dunnart, while also increasing our knowledge of native flora such as the unique Mount Finke Grevillea and Ooldea Guinea Flower.

‘Felixer’ devices use LIDAR and AI to distinguish foxes and cats from native species and remove the feral predators from the ecosystem. Felixers have been deployed across an area of more than 20,700 hectares and are targeting predators near active malleefowl mounds. Remote trail cameras have been placed to monitor mounds, enabling AW to record activity around the nests including breeding behaviours and the presence of predatory feral species.

AWLB also takes action to manage the threats from large feral herbivores, particularly camels, and buffel grass.

Through partnership with Anangu ranger groups and communities, AWLB’s Malleefowl project has successfully safeguarded Malleefowl habitat in our region, with a positive population trajectory for the Malleefowl themselves, as well as flow-on benefits for the myriad animals and plants they coexist with. It’s a successful multifaceted approach that must be maintained to continue these positive outcomes into the future.

AWLB General Manager Kim Krebs

The presence or absence of Malleefowl can be an indicator of the broader health of the ecosystem. Their ground-dwelling habits and nesting requirements mean they are susceptible to many threats facing landscapes. Protecting nganamara has many benefits for the landscape as a whole. If they can thrive, other species such as sandhill dunnarts are also likely to have improved chances for success.

Data is shared with the National Malleefowl Recovery team supporting delivery of the National Recovery Plan.

Although Malleefowl seem to be doing better in the AW region than the national average, they face threats on many fronts, such as feral predators, invasive buffel grass, large feral herbivores, and climate change. Continued monitoring and threat abatement are essential to safeguard this iconic species.

The trajectory of breeding Malleefowl population is at least stable, compared to the June 2019 baseline, because the number of active Malleefowl mounds increased at the 6 LiDAR sites over the last year of monitoring.

Prior to 2018, only 7 mounds were known from Maralinga Tjarutja lands. This increased to 19 mounds recorded in 2019 and 47 mounds in 2023 across the southern 2/3 of the AW region.

Across all the sites and all the years, the average percentage of active Malleefowl mounds compared to all surveyed mounds was around 28%, with some sites being active for four consecutive years. This is a huge proportion, showing that more than a quarter of all visited mounds in the AW region are active. This compares very highly to other cropping regions of Australia where only 2% of existing Malleefowl mounds may be active.

Using LiDAR, camera grids and undertaking on-ground sand plot surveys were the best methods to achieve this goal as many new active Malleefowl mounds were found across the southern 2/3 of the AW region, providing better knowledge of a stable Malleefowl population in the region.

In the future, using more LiDAR surveys and the current habitat knowledge could help identify more mounds.

Using drones with LiDAR technology could also be a more efficient way to look for Malleefowl mounds located outside the current LiDAR transects and more broadly to locate new sites across such a vast and remote region.

AWLB works alongside Anangu communities from the Far West Coast, Maralinga Tjarutja and APY Lands, providing training and support in survey methods, data management, and pest animal and plant control.